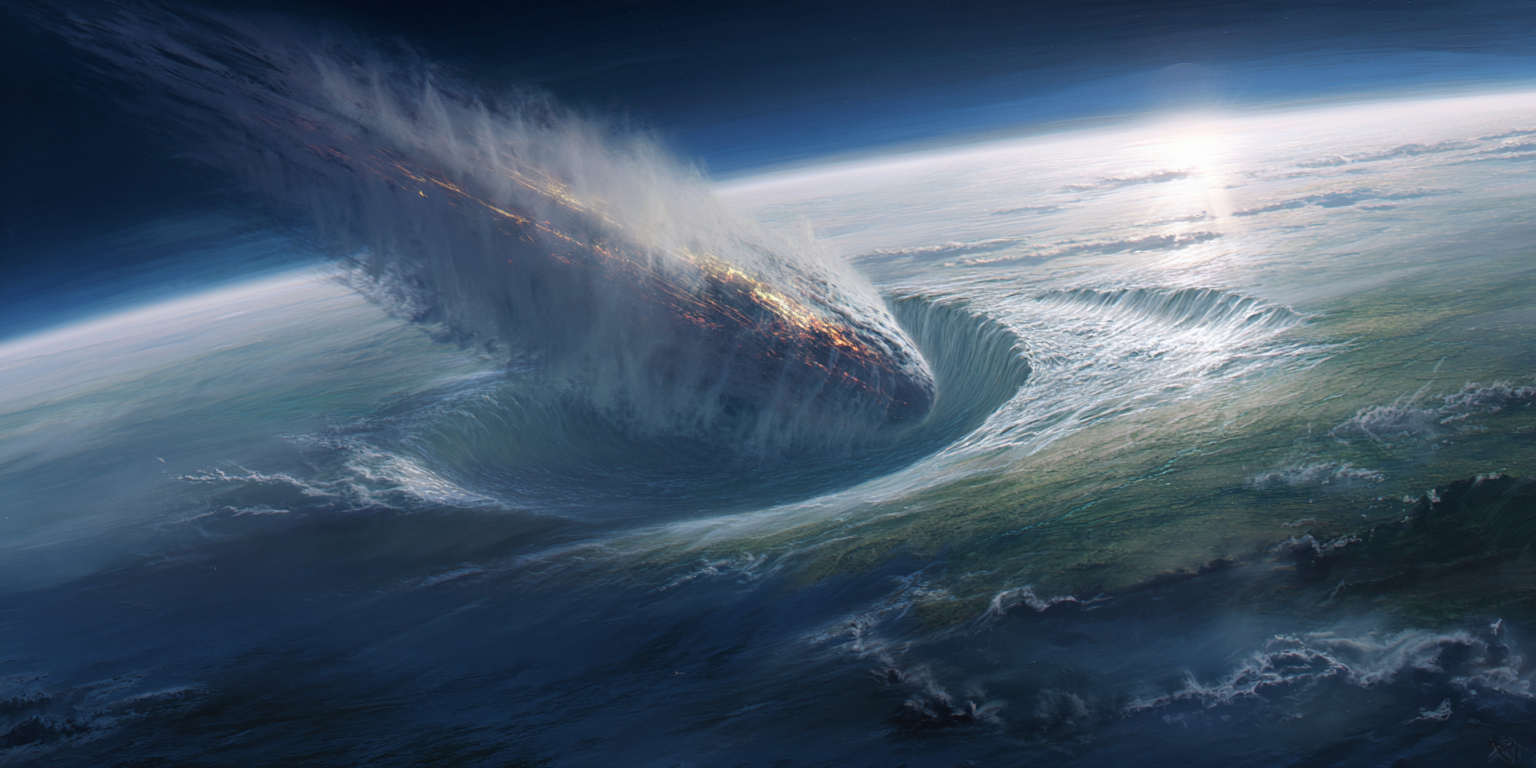

The extinction rate exceeds natural background levels by orders of magnitude. Entire ecosystems have crossed irreversible thresholds. If this is not a mass extinction, then the term may have lost its meaning.

Subscribe to continue →Yes, we are all going to die...