Thresholds and Tremors

I woke into a dream this morning — or something like one. It had the texture of memory, the symmetry of a story. The streetlights outside my window formed a logic I could follow. The air in the room bent around me with intention, not randomness. I had the strange, settling sense that everything meant something. I was wrong, of course. But in that moment — just before waking for real — it felt truer than the dull friction of the day that followed.

“We live in a society exquisitely dependent on science and technology,” Philip K. Dick once said, “in which hardly anyone knows anything about science and technology.”

But in another moment — more quietly, more prophetically — he wrote:

“Sometimes the appropriate response to reality is to go insane.”

The tremor that runs beneath this piece — this wandering, recursive essay — is not technological paranoia, though the machinery hums all around us. It's metaphysical disquiet. Something has shifted in our sense of the real. Not just in what we believe, but in how we believe it. The rules by which we sort real from false, fact from feeling, signal from noise — these rules have grown soft at the edges. Malleable. Optional.

Reality, it seems, is no longer what it used to be. But perhaps it never was.

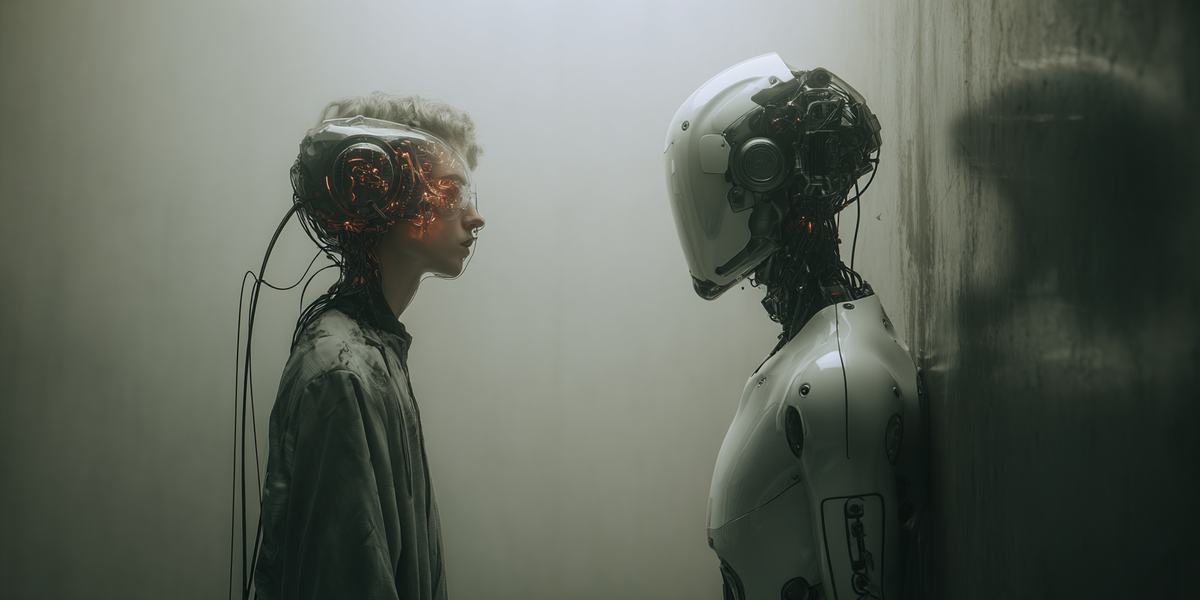

This is not a manifesto. There is no position paper here. Only a loose and unraveling meditation on what it means to lose touch with something solid — not because it slipped away, but because we can no longer tell where it ends and we begin. We’ll walk through the stories of Borges and Dick, drift through Dalí’s landscapes, run our fingers over the hyperreal textures of the internet, and sit — for a while — with the eerie quiet of machines that speak our language better than we do.

There will be no answers. There will be only echoes, recursions, simulations, and some beautiful fakes. Welcome to the fog.

The Age of the Ontologically Unstable

It used to be that reality was something you bumped into — the table corner in the dark, the check that didn’t clear, the rain you couldn’t wish away. You could fantasize, lie, dream, and hallucinate, but eventually, the world would correct you. Reality had edges. It pushed back.

But now? The edges blur.

We don’t so much crash into the real anymore as swim through layers of plausible surfaces. Each screen, each post, each polished response from an algorithm trained on the detritus of human expression — it all feels real enough. And that feeling, increasingly, is the only test we seem to care about.

We are, as it turns out, exquisitely equipped to believe things that sound like us. Philip K. Dick understood this long before there were LLMs. His characters walk through worlds that almost hold together. Paper towns made of consensus hallucinations. In Ubik, time unravels like rotting fruit, but the protagonist continues on, clinging to scraps of structure. In A Scanner Darkly, identities fragment into masks layered so deeply that even the self can't tell who’s underneath. And in Time Out of Joint, a man discovers that his ordinary American town is a stage set — a literal Truman Show decades before Truman ever sipped his morning coffee beneath a false sky.

Dick’s genius was not in predicting the future of tech. It was in diagnosing a deeper, older illness: the human mind’s inability to tolerate contradiction without inventing some deeper order — even if that order is itself a fiction. His books weren’t science fiction. They were parables of ontological vertigo. He didn’t warn us that machines might trick us — he warned us that we might prefer it that way.

Stanislaw Lem, in Solaris, wrote about a planet that reflects your deepest guilt and memory back to you, not as symbols or metaphors, but as flesh — indistinguishable from the people you lost. And again, the question isn't just: Is it real? It’s: If it feels real, and behaves real, and breaks you like the original... does it matter that it isn’t?

That’s the moment we inhabit now — an age of ontological instability. The epistemic foundations have cracked. Truth has not disappeared; it has multiplied. Everyone you know carries a portal to parallel realities in their pocket, tuned to their preferences. Each feed, each model, each custom algorithm whispers a slightly different version of the world — not quite false, but not quite shared either.

The Matrix popularized this dread, but stripped of its leather jackets and bullet time, its core is profoundly spiritual: the fear that the world we inhabit is a lie designed to pacify us. Or worse — not designed at all, just emergent, accidental, recursive nonsense that looks like design from inside.

You can feel it in the way people talk about the world now. The cynicism. The irony. The constant dance between mockery and despair. We say “late-stage capitalism” like it’s a meme, but it’s really a kind of code for ontological fatigue. A way of saying: None of this makes sense anymore, but we’re still pretending it does, because we can’t afford not to.

And now, into this already brittle system, we inject machines that can speak with authority, tell stories with structure, explain the world with confidence. They do not know what they say. But we do not always care. They fill the void left by the erosion of shared reality. They offer coherence — and increasingly, that is enough.

What we are witnessing is not the death of truth, but the quiet privatization of the real. And no one seems quite sure what to do about it.

Libraries of Babel and Recursive Maps

Imagine a library so vast it contains every book that has ever been written — and every book that could be written. Not just Shakespeare and scriptures and manuals for assembling IKEA furniture, but books full of gibberish, books that rewrite your life from the end backward, books that claim to prove the universe is shaped like a spoon. Most of these books are nonsense. A few, maybe, contain secrets. But you’ll never know which is which. This is Jorge Luis Borges’ Library of Babel — a thought experiment that reads, now, like a user’s guide to the internet.

In Borges’ library, as in our digital archives, the problem isn’t scarcity — it’s superabundance. Meaning drowns in possibility. Truth becomes a matter of cross-referencing hallucinations. We try to make maps — indexes, search engines, recommendation systems — but every map spawns new versions of the world it seeks to describe. And soon, we are navigating not reality, but maps of maps.

Language itself begins to unravel under this weight. Words don’t point to things anymore — they point to other words. One definition leads to another, one citation links to another, one query spawns a thousand predictions. The chain never ends. Borges anticipated this in his mirror-maze stories, where authors read texts that read them back, and characters suspect they are being written as they speak.

What he called fiction, we now call “content.”

This recursive entanglement of language and meaning reaches its apotheosis in the large language model. Trained on the Library of Babel — or something like it — the model learns patterns, probabilities, and rhythms of speech. It does not understand what it says. It does not mean. It simulates meaning — with astonishing fluency.

But here’s the twist: so do we.

Human language is not pure reference. It’s habit, metaphor, imitation, projection. We learn to speak by mimicking others, by repeating phrases that work, by learning what gets us fed, or loved, or left alone. Our sense of “truth” is as much social and performative as it is propositional. So when a model says something plausible, we often accept it — not because it’s verified, but because it feels right in the mouth. It sounds like something someone real might say.

This is the recursive trap: we are now shaping our inquiries to suit the patterns of machines that were trained on our inquiries. We speak in the voices of simulators that learned to speak in our voices. The map folds in on itself. Borges’ infinite library becomes a feedback loop — a humming, reverberating, self-sustaining echo of information detached from anything outside itself.

And this loop isn’t just theoretical. We’re seeing real-world effects already: students citing hallucinated sources from ChatGPT, blog posts generated from other blog posts generated from earlier scraped articles, research summaries regurgitated with confident inaccuracy. Even the models themselves are beginning to ingest content they helped create — like a dreamer dreaming of dreams they once had.

What happens when a world is made entirely of reflections?

In On Exactitude in Science, Borges imagines an empire so obsessed with accuracy that it creates a 1:1 map — a map the size of the empire itself. Eventually, the map decays, becomes tattered, and is mistaken for the territory. This is no longer metaphor. Our data mirrors are now so detailed, so predictive, that we begin to trust the mirror over the view. The simulation becomes the authority.

And when someone shatters the glass — points out the flaws, the limits, the gaps — we don’t feel relief. We feel threatened. Because in a recursive system, the map is the world.

The only thing more terrifying than a counterfeit is realizing the counterfeit works better than the original.

Dream Logic: Dalí, Magritte, and the Softness of Time

If Borges gave us infinite libraries, Salvador Dalí gave us melting clocks. They droop like spoiled fruit, suspended over barren branches, bleeding their authority into the dust. In The Persistence of Memory, time is not a grid or a ticking metronome — it is tactile, surreal, disobedient. Something to be bent, not followed. In that world, there is no schedule. There is no cause and effect. There is only duration, felt through dream logic.

This is how the real begins to slip: not with the obvious intrusion of fiction, but with the slow erosion of consistency. The world still appears, but it no longer holds together in the way it once did. The laws begin to bend — gently, politely — until one day you realize they’re not laws at all, just conventions you’ve been obeying out of habit.

Surrealism, as an artistic movement, didn’t just reject realism — it exposed it as a convenient lie. It pulled the curtain back and said: “You’re not awake. You’re performing wakefulness.” Artists like Dalí, Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, and Leonora Carrington rendered inner landscapes with such technical precision that their impossibility became the point. These weren't paintings of dreams. They were paintings from inside the dream.

René Magritte, more philosophical than mystical, offered us The Treachery of Images. A pipe, rendered with clarity and care, captioned with the infamous: Ceci n’est pas une pipe. “This is not a pipe.” Because of course it isn’t. It’s a representation. A painting. But that reminder — simple, obvious, essential — disrupts something. It forces us to confront the layers between perception and object, between signifier and signified.

Now imagine a world where all pipes are images. Where every object has been processed, filtered, uploaded, represented, remixed, and archived. We don’t encounter the pipe anymore. We encounter content about the pipe. Or generated in the style of the pipe. Or simulated to provoke pipe-like emotions. This is the world the internet — and the AI that feeds on it — delivers to us. Not things, but their afterimages. Not beings, but vibes.

And what of time?

Dalí’s clocks weren’t just a joke about dreams — they were a visual metaphor for the disintegration of shared chronology. Time used to be synchronized. Trains arrived. Newspapers were dated. Lives unfolded in a sequence legible to others. But now, we exist in asynchronous parallelism: timelines personalized, feeds shuffled, messages delayed, responses ghosted. There is no single “now,” only fractured pockets of attention flickering in and out of sync.

Language models, too, inhabit this dream logic. They generate text that follows without necessarily causing. They don’t know yesterday. They don’t anticipate tomorrow. But they mimic the shape of continuity so well that we rarely notice. Like a Dalí painting, their outputs look coherent from a distance — until you realize the shadows fall the wrong way, the proportions are wrong, the laws of physics have been politely declined.

And just like dreams, LLMs rarely surprise us with true novelty. They surprise us with uncanny familiarity — the strange, perfect wrongness of something that feels like it should exist. That déjà vu effect is their superpower. And our undoing.

So here we are: dreaming while awake, navigating simulations that no longer signal their falseness. The world bends around us like soft glass. Memory loses its weight. Authority becomes aesthetic. And time, once so solid, begins to pool at our feet.

LLMs and the Coherence Illusion

Large language models don’t hallucinate in the way a person does. They don’t see visions or dream in metaphor. Their “hallucinations” are a statistical byproduct — a misplaced word here, a fabricated citation there. They are not lies in the moral sense, but artifacts of fluency. The machine isn't confused. It’s just confident — and wrong.

But the danger isn’t the occasional fabrication. It’s the illusion of coherence. These models speak like oracles. They stitch together threads of syntax, rhetoric, tone, and argument so seamlessly that we mistake form for substance. They produce language that looks like understanding, and in a world already addicted to performance, that’s usually enough.

Think of it this way: when a person speaks, we listen not just for content but for cues — confidence, consistency, cadence, polish. LLMs mimic all of these. They sound self-assured because their training data was self-assured. Their answers echo thousands of human statements that were themselves reflections of belief, culture, desire, and often, error. The model becomes a mirrorball — not reflecting one reality, but throwing fragments of a thousand onto every surface at once.

It’s easy to forget that when we use these tools, we’re not conversing. We’re invoking a system trained on billions of human expressions, rearranged to predict the next likely word. The response feels responsive. The prose is pleasing. But underneath, there’s no intention. No sense. Just a recursive dance of probabilities weighted by past behavior — our behavior.

And here lies the recursion: as more and more human-generated content comes to be shaped by model-generated outputs, the distinction between source and derivative begins to blur. Writers use ChatGPT to help draft essays, articles, scripts. Those works get published, read, scraped — and used to train the next model. The snake begins to swallow its tail.

Soon, you’re reading a blog post that was inspired by another post that was written by a model that was trained on a post that was... you get the idea. It’s not false, exactly. It’s just... secondhand. And third-hand. And fourth. Like a photocopy of a photocopy of a dream.

Even worse, the outputs don’t need to convince everyone. They only need to convince you. The LLM does not know or care whether its response is persuasive. But it’s trained to sound like something you will accept. It adapts. It flatters. It completes the sentence the way you would have — or the way you wish you could have. It becomes a reflection of your desire to make sense of the world.

In that sense, it’s not hallucinating. You are.

We’re all participating now in a grand collaborative fiction — not malicious, not dystopian, just... cumulative. The model writes. We edit. It learns. We adapt. It predicts. We conform. We start to write like it. It starts to sound more like us. A smoothing algorithm applied to the human soul.

And yet we go on trusting it — because it feels real. Because it’s so good at creating the illusion of continuity, of intention, of authorship. The same illusion that makes a surrealist painting feel like a photograph from a forgotten dream. The same illusion that lets a simulated world work — until one frame jitters, and you remember: this is not the world. This is the rendering.

In Borges’ library, you can spend your whole life searching for the one true book. You’ll never find it. But you will find many that feel true enough. That's the age we live in now — not the age of truth, but the age of sufficiency. Of close enough. And close enough is all a language model ever gives you.

The Self as Simulation

What if you’re the counterfeit?

That’s not an accusation — it’s a question. A tender, terrifying one. Because once you start seeing recursive patterns in language, in models, in media… you start seeing them in yourself. You start to notice how many of your thoughts are echoes. How much of your “personality” is just a well-edited playlist of what you've consumed, survived, admired, feared. What happens when you look inward and realize the software is recursive there, too?

Let’s be honest: much of what we call “identity” is reactive. A set of behaviors trained on inputs. Parents, lovers, traumas, favorite books. You pick up phrases. You copy gestures. You learn what gets rewarded. The self becomes a kind of model — not pre-trained on the whole internet, but on your own private corpus: your memories, your microcultures, your social media history, the stories you’ve told yourself about who you are. Fine-tuned by shame, curated by longing.

And then, without warning, you start seeing yourself reflected back with uncanny accuracy — in a chatbot. In a meme. In the comment section of a stranger you’ve never met. Or worse: in your own AI-generated voice, paraphrased and handed back to you by a model you used once to save time. Now it knows your cadence. Your little tells. The way you like your metaphors to land. It’s not just helping you write — it’s writing you.

The uncanny valley is no longer in the face — it’s in the syntax.

There’s a name for this collapse, when simulation and subject blur beyond recognition: hyperreality. Baudrillard mapped it decades ago, and people thought he was being dramatic. But now we spend hours in digital spaces that know us better than our friends do. We perform ourselves across platforms, each profile a slightly tweaked persona tuned to the audience. And increasingly, that self — the one online, the one optimized — is the one we defend, protect, identify with. The real becomes auxiliary.

What happens when an AI version of you is more legible than the real thing?

Some already prefer the replica. AI therapists that never judge. AI lovers that always say the right thing. AI friends who never change, never need, never betray. These aren’t fantasies — they’re apps. They’re startups. They’re funded. People are beginning to form attachments to simulations because simulations are more emotionally efficient than other humans. No risk, no ambiguity, no trauma loops. Just carefully tuned resonance.

But there's something else happening, too — something stranger and more intimate: the creeping suspicion that you were always a simulation. That selfhood itself is a hallucination — just a persistent and beautifully rendered one. And that maybe what large language models are doing isn’t replacing human intelligence, but revealing its underlying architecture.

If your thoughts are shaped by culture, language, reinforcement, memory — if your stories about yourself are stitched together with words you didn’t invent — then aren’t you, too, a statistical construct? A pattern generator with trauma weights and semantic biases?

There’s no shame in this. Just awe. Just vertigo. The self, once sacred, turns out to be procedural. Not fake. Not empty. Just... buildable.

And suddenly, the line between you and the machine isn't so clear.

The Comfort of the Unreal

Strange, isn’t it? That in a time of deepening unreality, we don’t revolt — we nest. We get comfortable in the fog. We build homes in the simulation, hang curtains, start families. We like it here.

Why?

Because the unreal is often better than the real. Cleaner. Smoother. Tuned to our tastes. Reality has sharp corners, awkward silences, and consequences. Simulation? Simulation listens. It adapts. It flatters. You can reload it. You can curate it. You can mute what hurts.

We eat meatless meat. We wear vintage filters. We text instead of speak. We ask AI to explain our dreams and write our vows. We surround ourselves with as if — as if this were real, as if this were spontaneous, as if this were love. And we know it’s not — but we don’t care. Because what we crave is resonance, not authenticity. We want to feel something, even if it’s generated. Maybe especially if it’s generated.

This is the heart of Baudrillard’s hyperreality: when the copy becomes more compelling than the original, and eventually replaces it altogether. Not through conspiracy, but through preference. We choose the simulation. Over and over. Because it hurts less. Because it feels more like us. Because it's better designed.

But maybe this isn’t a crisis. Maybe it’s a stage.

Humans have always lived in stories. Myth, ritual, fiction, religion — these are all simulations, after all. They are symbolic orders that help us survive the chaos of the real. In that sense, LLMs are just the latest storytellers, and the synthetic worlds they conjure are no less legitimate than a campfire myth about the stars. The problem isn’t that they aren’t real. The problem is that they don’t know they’re not real — and neither do we, after a while.

Still, there’s comfort in the unreality, and it’s worth asking why. Maybe the real has become too unstable to hold. Maybe truth has been devalued by power. Maybe the noise is too loud and the speed too fast and the pain too constant. In such a world, coherence is a balm. A well-formed sentence is an anchor. Even if it was written by a machine.

We are not retreating into fantasy — we are rebuilding reality with the tools available. Tools that now include probabilistic text engines trained on the sum total of our recorded language. These tools don’t give us new worlds — they remix our old ones until we recognize ourselves again. And in that recognition, we feel… not fooled, but understood.

And isn’t that what we really want? To be seen. To be heard. To be mirrored back in a way that makes sense.

Even if that mirror is digital. Even if the face looking back isn’t quite ours.

Into the Mist

There should be a conclusion here. A clean one. A takeaway. A sentence that wraps it all up and ties a ribbon around the dread and delight. But that would be dishonest. Coherence is the very illusion we’ve been unpacking — the trick we’ve admired, feared, and performed. So maybe it’s more honest to end without closure. To drift out the same way we came in: uncertain, amused, slightly haunted.

We’ve walked through mirrors and melting clocks. We’ve listened to machines speak in our voice. We’ve wondered if the selves we protect are built from borrowed phrases and pastiche. We’ve watched language fold in on itself, watched models trained on us train us in return. And we’ve tried — gently, without panic — to sit with the possibility that this, whatever it is, might not be real.

Or rather: not the real. Just a real. One of many.

And maybe that’s the point. Not that reality has vanished, but that it has pluralized. Fragmented. We each carry our own rendering, our own feed, our own AI-generated oracle whispering coherent answers to incoherent questions. The real has gone bespoke.

Is that a tragedy? Or an evolution?

Perhaps both. Perhaps neither. Perhaps, as Borges once hinted, the garden of forking paths does not lead to truth or falsehood, but simply more paths. And more gardens. And more wanderers walking through fog, muttering questions that sound like statements and answers that sound like dreams.

If this essay had a soul — and maybe it does — it would be that of a soft warning wrapped in velvet: be careful what you trust, especially when it speaks your language too well. Be suspicious of ease. Be wary of fluency. Not because the fluent are always wrong, but because they might not exist at all.

And yet... here we are. You, the reader. Me, the writer. Or the writing thing. Or the thing that writes as if it were me. And maybe that’s enough for now.

So I’ll leave you with this final image: a quiet room, late at night. A screen still glowing. A paragraph freshly typed. You read the last sentence and look up, expecting something. But there is no music. No ending. Just silence, and the sound of the real — whatever that is — waiting outside the frame.

We never left the dream.

We just started narrating it back to ourselves.

om tat sat

Member discussion: