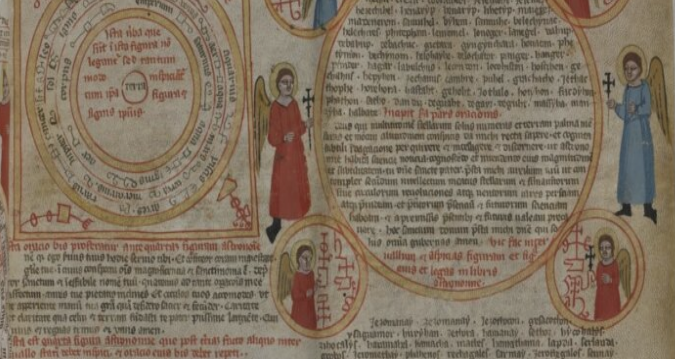

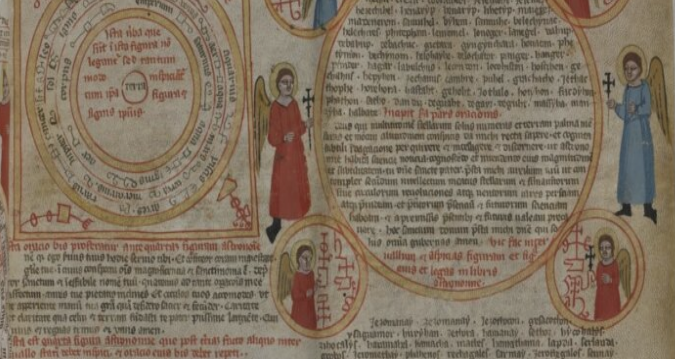

Few works in the history of Western occultism are as imposing, enigmatic or foundational as the Summa Sacra Magice of Berengarius Ganellus.

Subscribe to continue →The Summa Sacra Magice of Berengarius Ganellus

Few works in the history of Western occultism are as imposing, enigmatic or foundational as the Summa Sacra Magice of Berengarius Ganellus.

Subscribe to continue →