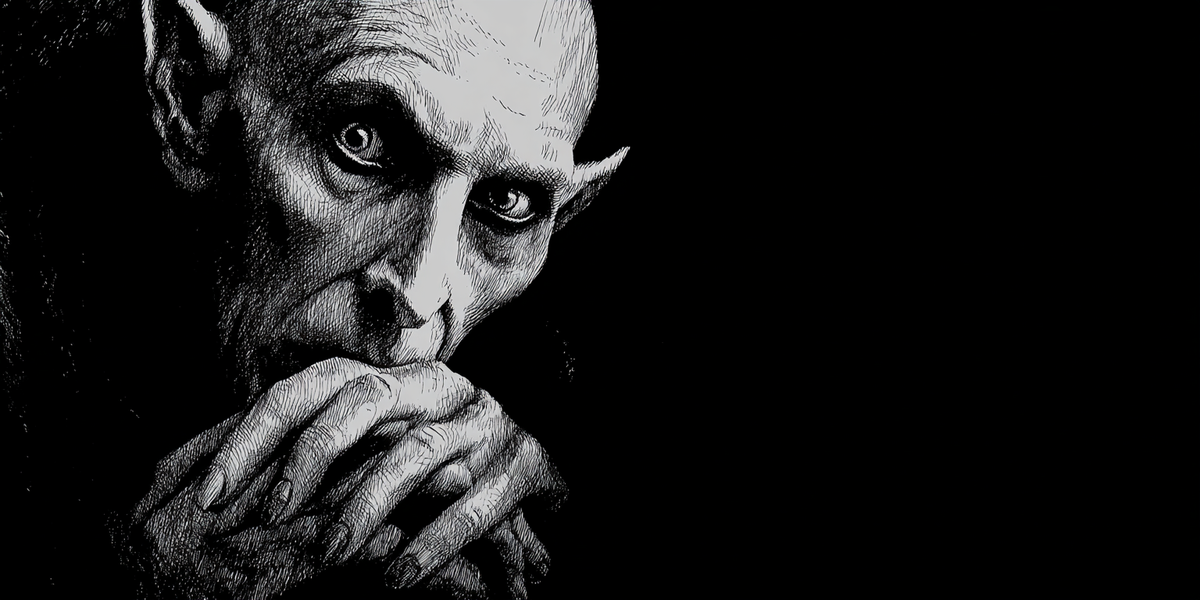

In Henrik Galeen’s adaptation, filtered through the haunted lens of German Expressionism, the vampire was reborn as a figure of plague, shadow, and inevitable doom.

Subscribe to continue →The enduring legacy of F. W. Murnau's seminal 1922 classic, "Nosferatu"