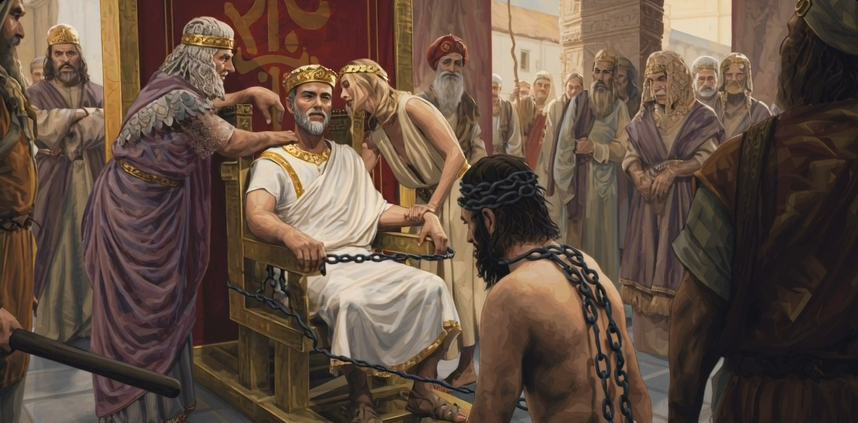

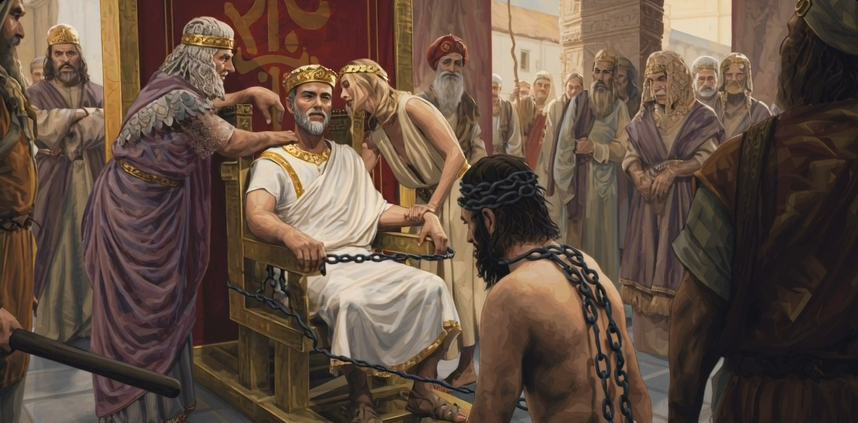

The Gospels give Pilate’s wife barely a whisper of a voice, but it is one that has echoed across centuries of Christian imagination.

Subscribe to continue →Pilate’s Wife: From a Dream in Matthew to a Saint in Legend

The Gospels give Pilate’s wife barely a whisper of a voice, but it is one that has echoed across centuries of Christian imagination.

Subscribe to continue →