Lovecraft's praise of Frankenstein turns caveat with: "...despite its more or less mechanical plot and clumsy epistolary form." This is rich, coming from a man whose idea of narrative sophistication was to have a trembling narrator write down a ten-page panic attack before being eaten by an idea.

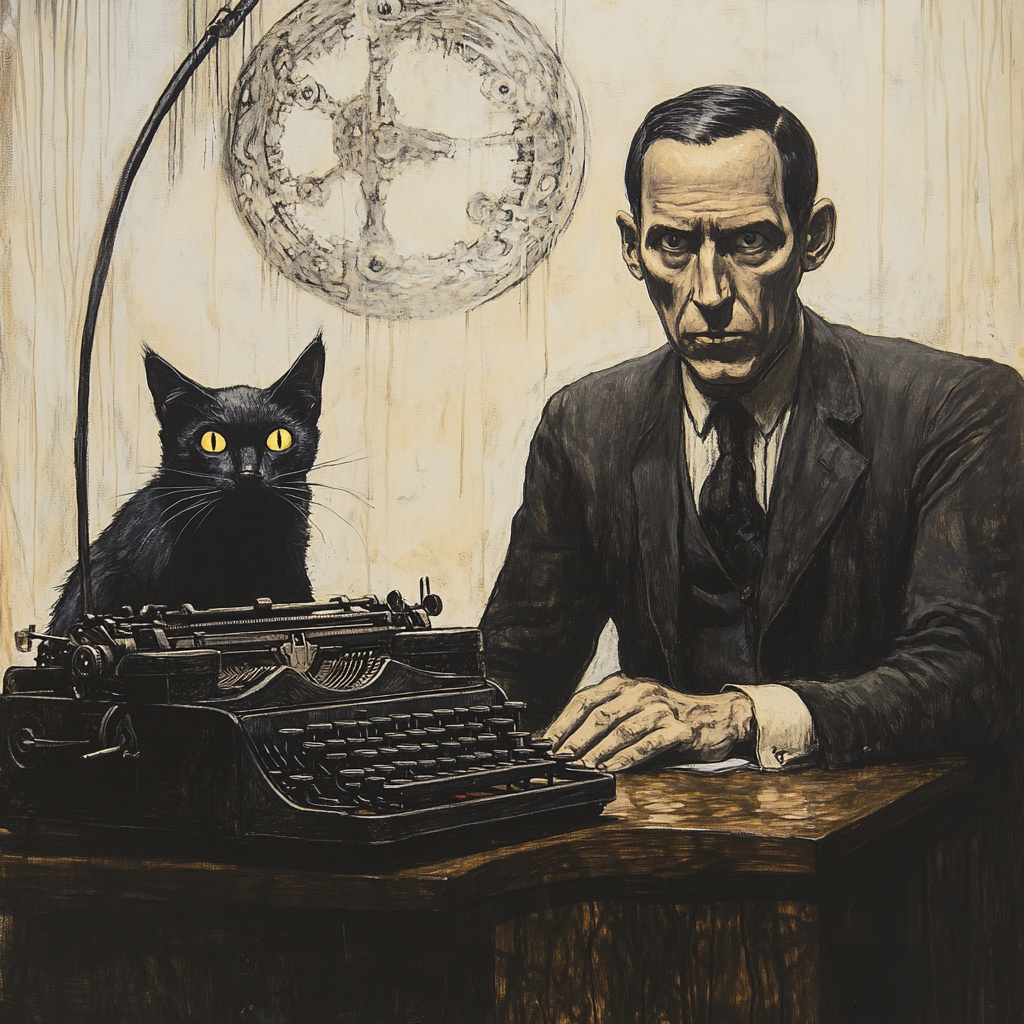

Subscribe to continue →Of tentacles and sour grapes: Lovecraft’s side-eye at Mary Shelley