In the age of large language models, where synthetic text flows with eerie coherence and casual eloquence, the line between authored and generated has blurred beyond easy recognition...

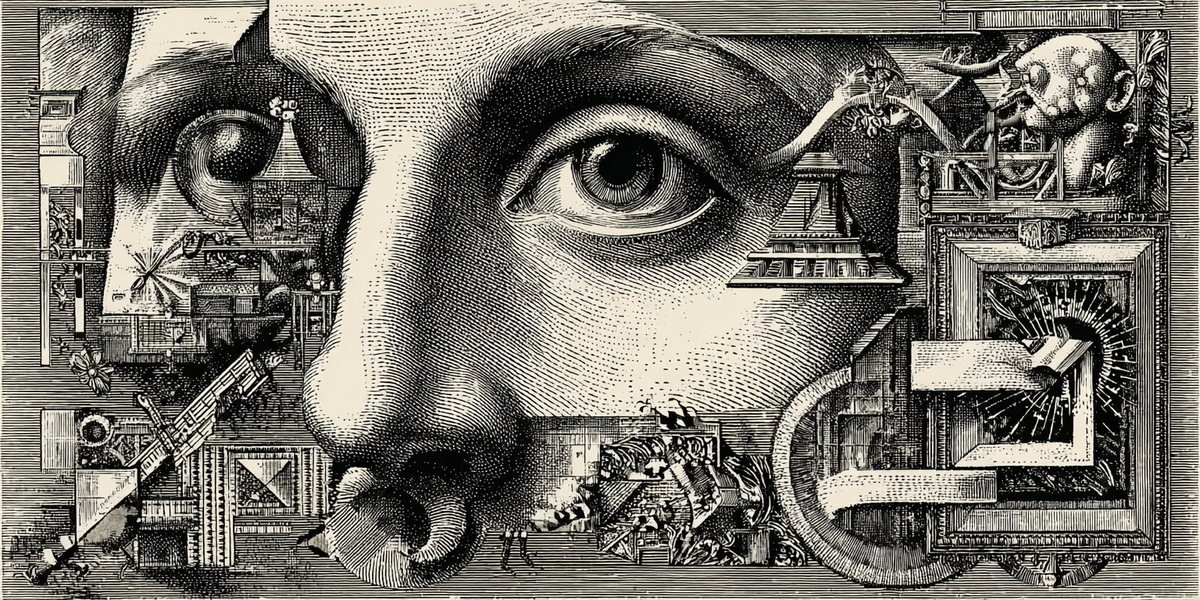

Subscribe to continue →Obfuscated markers as subtle confessions of artificiality