The Cosmology Contradiction

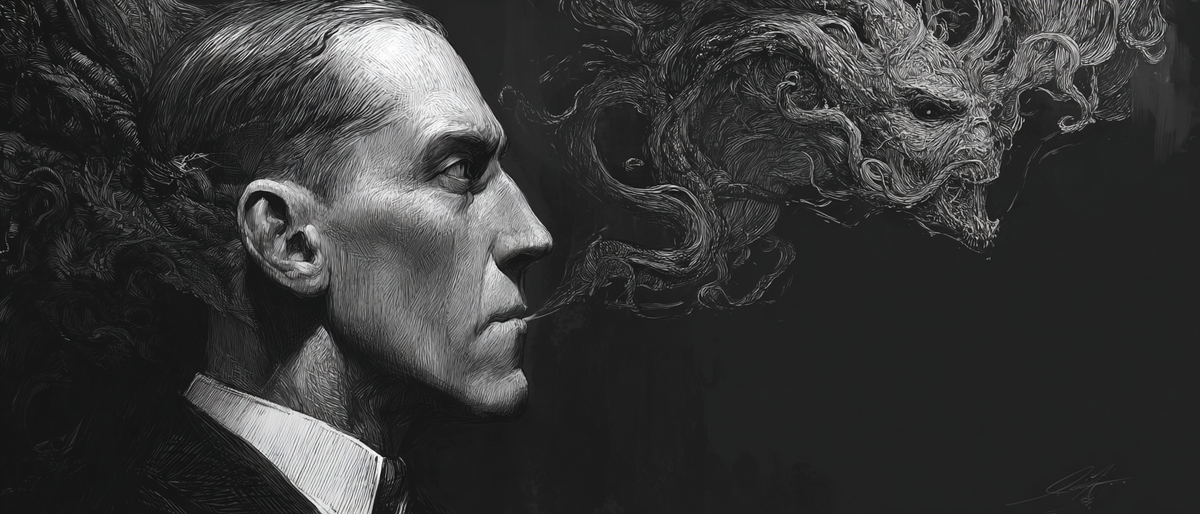

If you know H.P. Lovecraft at all, you probably know him as the prophet of cosmic horror—the man who gave us Cthulhu, the writer who insisted that humanity is cosmically insignificant, adrift in an indifferent universe where ancient gods sleep and knowledge leads to madness. His famous declaration from 1927 seems to sum up his entire worldview: “All my tales are based on the fundamental premise that common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large.”

This is the Lovecraft we’ve been taught to read: the cold materialist, the scientist of the weird, the man who weaponized existential dread into fiction.

But there’s another Lovecraft—one that academic criticism has largely overlooked, dismissed, or actively suppressed. And the key to finding him lies in the work that scholars have traditionally treated as an embarrassing detour: The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath.

The Philosophy He Preached vs. The Philosophy He Lived

Here’s the contradiction at the heart of Lovecraft’s life: the man who wrote about cosmic meaninglessness lived one of the most meaning-saturated existences imaginable. While his published horror stories depicted a universe empty of value, his private life overflowed with passionate devotions.

He didn’t just live in Providence, Rhode Island—he was Providence, as he himself declared in a letter to James Morton in 1929: “I am Providence.” He took ritualistic night walks through its colonial streets, communing with what he called “the ghosts of our forefathers.” He maintained an enormous correspondence network, writing thousands of letters to friends, mentoring younger writers, forming deep emotional bonds. He poured his soul into preserving the memory of 18th-century New England, lamenting every demolished colonial house as if a piece of his own body were being torn away.

This is not the behavior of someone who truly believed nothing matters.

And nowhere is this contradiction more nakedly exposed than in The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, a work that Lovecraft wrote in 1926-27 but never published, never even tried to publish, calling it merely an “unpolished” draft. The story follows Randolph Carter—Lovecraft’s recurring alter-ego—on an epic quest through the dreamlands, searching for a city of impossible beauty he glimpsed in a dream.

Kuranes and the Radical Choice

Early in the narrative, Carter encounters Kuranes, a dreamer who made a choice that should be impossible within Lovecraft’s stated philosophy: after dying in the waking world, Kuranes chose to remain in the dreamlands forever, ruling over the cloud-city of Celephais rather than facing oblivion.

Read that again. One of Lovecraft’s characters—not a villain, not a figure of horror, but a sympathetic, even admirable character—actively chooses subjective beauty over material reality. He chooses the dream over the “real.” He chooses meaning over mechanism.

This is not a small thing. This is Lovecraft admitting, through the structure of his fantasy, that subjective experience can matter more than objective existence. That beauty, memory, and chosen reality can have a validity that transcends mere material fact. Kuranes doesn’t go mad from this choice. He doesn’t degenerate. He doesn’t suffer cosmic punishment. He simply... lives in beauty. Forever.

Try to square that with “cosmic indifferentism.” You can’t.

The Dream is Real; Reality is a Dream

What Lovecraft reveals in Dream-Quest—inadvertently, perhaps, or perhaps with full awareness of what he was confessing—is that his cosmic horror was always a kind of defense mechanism. The horror of an indifferent universe is easier than the horror of caring deeply about things that will inevitably be lost. It’s safer to say nothing matters than to admit that Providence matters so much it hurts.

His cosmic horror stories are brilliant, yes. They’re formally accomplished, culturally influential, and genuinely terrifying. But they’re also evasions. They allow Lovecraft to explore his fears while maintaining emotional distance. The narrator goes mad; Lovecraft remains untouched.

Dream-Quest offers no such distance. It’s a story about longing—pure, undefended longing—and longing reveals more about a person than fear ever could.

When Carter finally reaches the mysterious Kadath and confronts Nyarlathotep, he discovers that the “sunset city” he’s been seeking across vast dream-realms is not some distant paradise. It’s the streets of his own childhood. It’s Boston and Providence, transfigured by memory into something radiant and eternal. The quest for transcendence leads him home.

This is Lovecraft’s actual cosmology, the one he lived by even as he denied it in his horror fiction: home is sacred, memory is real, beauty justifies existence, and the familiar can contain the infinite.

Why This Matters for New Readers

If you’re coming to Lovecraft for the first time, you’ve probably been directed toward the “essential” stories: “The Call of Cthulhu,” “The Colour Out of Space,” “At the Mountains of Madness.” These are the works that built his reputation, the ones that defined cosmic horror as a genre.

But starting there gives you an incomplete—in some ways distorted—picture of who Lovecraft was. You’ll meet the intellectual, the theorist of dread, the architect of alien geometries. You won’t meet the man who wept over demolished buildings, who signed his letters with absurd Gothic flourishes, who told his correspondents that their friendship was “the brightest moment of my day.”

The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath is the secret doorway into the complete Lovecraft. It’s the work where his two selves—the cosmic pessimist and the sentimental mystic—finally converge. It’s the only story where he lets both truths stand: yes, the universe is vast and indifferent, and your childhood home is the center of all meaning.

This isn’t a contradiction. It’s a paradox. And paradoxes are where the deepest truths live.

In the sections that follow, we’ll explore how Dream-Quest reveals Lovecraft’s idealized self-portrait through Randolph Carter, how the choice of fantasy over horror represents a confession rather than an evasion, how the work’s ambitious structure attempts something his horror stories never could, and ultimately, why this “unpolished” draft he never dared to publish might be the most complete artistic statement he ever made.

But first, you need to understand this: Lovecraft’s philosophy and Lovecraft’s life were fundamentally at odds. And when an artist’s life contradicts their stated beliefs, always trust the life. Always trust what they do over what they say.

Dream-Quest is what Lovecraft did when he stopped trying to be the prophet of meaninglessness and simply became himself.

Randolph Carter as Lovecraft’s Idealized Self

Most of Lovecraft’s protagonists don’t fare well. They go mad. They discover terrible truths about their ancestry. They stumble upon forbidden knowledge and pay the price. The typical Lovecraft narrator ends the story broken, insane, or dead—a victim of cosmic forces beyond human comprehension.

Randolph Carter is different.

Carter appears in multiple Lovecraft stories, but The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath gives us his fullest portrait—and in doing so, reveals something Lovecraft rarely allowed himself to express: what he looked like when he imagined himself as a hero rather than a victim.

The Virtues of the Dreamer

Carter’s journey through the dreamlands isn’t accomplished through violence, wealth, or supernatural power. He succeeds through a specific set of qualities—and when you map those qualities against Lovecraft’s own life, the correspondence is unmistakable.

Physical Endurance Despite Setbacks

Carter’s quest is grueling. He crosses deserts, climbs impossible mountains, endures capture and enslavement, faces cosmic terrors. He’s knocked down repeatedly—but he never stops moving forward.

This is Lovecraft’s self-portrait as a writer. By the time he wrote Dream-Quest in 1926-27, he had endured poverty, the humiliation of his failed marriage to Sonia Greene, the loss of his family’s wealth, countless story rejections, and the constant awareness that his fiction was too strange for mainstream success. His letters from this period are filled with melancholy, yet he never stopped writing. He never stopped corresponding. He never stopped walking his beloved Providence streets at night, preserving what he could of the past through the sheer force of his attention.

Carter’s refusal to surrender—even when the quest seems hopeless—mirrors Lovecraft’s own dogged persistence. He kept creating not because success was likely, but because the act of creation itself was meaningful.

Diplomatic Skill and Alliance-Building

One of the most striking aspects of Carter’s journey is how often he succeeds through conversation rather than combat. He gains passage on ships by befriending captains. He earns the trust of ghouls who become his allies. He navigates the political complexities of the dreamlands through charm, respect, and careful negotiation.

This is not the skill set of a typical fantasy hero—but it’s exactly how Lovecraft himself operated in the world.

His vast correspondence network wasn’t just a hobby; it was how he survived. He mentored younger writers like Robert Bloch, August Derleth, and R.H. Barlow not out of obligation but genuine generosity. He formed deep friendships through letters, creating a literary community that sustained him emotionally and intellectually. When he had no money, he had friends. When he felt isolated in a modernizing world, he had correspondents who shared his loves and understood his references.

Carter’s ability to forge alliances across the dreamlands—with cats, with ghouls, with merchants and sailors—is Lovecraft celebrating his own greatest real-world skill: the ability to find kinship across apparent difference.

Compassion Across Hierarchies

Carter shows kindness to creatures both high and low. He befriends cats, who become his most loyal allies. He shows compassion to the mischievous, dangerous zoogs when he could simply avoid them. Most tellingly, when he’s enslaved by moon-beasts, he doesn’t forget the suffering of his fellow captives—he actively works to free them, even when it complicates his own escape.

This reflects something crucial in Lovecraft’s letters: despite his often-terrible political views and racial prejudices (which we cannot and should not ignore), his personal correspondence shows genuine warmth toward individuals regardless of their social status. He mentored working-class writers. He wrote encouraging letters to teenagers. He showed patience with amateur poets and struggling artists.

Lovecraft’s cosmic horror often depicts humanity as insignificant, but Carter’s compassion suggests the opposite: that even small acts of kindness matter, that dignity should be extended to all beings, that suffering deserves acknowledgment. The man who wrote “cosmic indifferentism” couldn’t stop himself from caring about the zoogs.

Solitary but Not Isolated

Carter travels alone through most of Dream-Quest, but he’s never truly isolated. He’s constantly encountering helpers, guides, and allies. He moves through a world that responds to him, that offers aid when he needs it, that recognizes his quest as worthy.

This is exactly how Lovecraft lived: reclusive but surrounded by a network of connection. He rarely left Providence, yet his letters reached across the country and the world. He was socially anxious, yet he maintained dozens of active correspondences. He was economically marginal, yet he was emotionally rich.

The model of heroism Lovecraft creates in Carter isn’t the solitary genius who needs no one—it’s the solitary traveler who knows how to receive help, who builds relationships that sustain him on his journey. Carter succeeds not because he’s self-sufficient, but because he’s worthy of aid.

The Hero Who Succeeds Through Virtue

Here’s what makes Carter so different from Lovecraft’s other protagonists: he doesn’t go mad. He doesn’t die. He doesn’t suffer cosmic punishment for his hubris.

He wins.

Not through luck or power, but through the consistent application of admirable qualities: persistence, diplomacy, compassion, and the wisdom to recognize when he needs help. When he finally confronts Nyarlathotep and the crisis of his quest, he survives because of choices he made earlier—alliances he forged, kindnesses he extended, respect he showed to beings others might have dismissed.

This is a genuine hero’s journey, and the hero is Lovecraft’s idealized version of himself.

Not Lovecraft the racist (those views appear elsewhere, poisoning other works). Not Lovecraft the pessimist. But Lovecraft the correspondent, the mentor, the friend, the man who found beauty in memory and meaning in place. Lovecraft the person who, despite everything, kept walking forward.

The Quest for Home

The most profound aspect of Carter’s characterization is what he’s searching for. He’s not seeking power, wealth, or forbidden knowledge. He’s searching for beauty—specifically, for a city he glimpsed in a dream, a place of such radiant perfection that waking life feels diminished in comparison.

This is Lovecraft’s actual quest, the one that animated his real life: the search for aesthetic and historical beauty in a world increasingly hostile to both. His long walks through Providence weren’t tourism; they were pilgrimages. His letters describing colonial architecture weren’t merely descriptive; they were acts of preservation, attempts to hold in language what the wrecking ball was destroying in fact.

And just as Carter discovers that his “sunset city” was his own childhood home all along, Lovecraft spent his life circling back to the same revelation: that Providence itself, properly seen and remembered, contained everything he was searching for. He didn’t need to discover new worlds; he needed to see clearly the world he’d been born into.

Why This Matters

When we read Lovecraft’s horror fiction, we meet protagonists who are punished for their curiosity, destroyed by their discoveries, broken by forces beyond their control. These stories are powerful, but they teach us that seeking leads to suffering, that knowledge brings madness, that we’re all doomed anyway.

Dream-Quest teaches something else: that persistence pays off, that kindness creates allies, that compassion matters, that the quest itself—even when difficult—is worthwhile. And most radically: that what we’re searching for might be waiting in the place we started, if we can learn to see it properly.

Randolph Carter is Lovecraft’s secret answer to all his cosmic pessimism. He’s the proof that Lovecraft knew, at some level, that his philosophy of meaninglessness didn’t describe the life he was actually living.

Carter doesn’t just survive his quest. He completes it. He finds what he was looking for. And in doing so, he becomes the hero Lovecraft couldn’t allow himself to be in his published horror—but desperately wanted to be in his private life.

This is why Dream-Quest matters more than academic critics have acknowledged. It’s not juvenilia. It’s not an embarrassing fantasy detour. It’s Lovecraft admitting what heroism actually looks like: not cosmic defiance, but human virtue. Not the rejection of meaning, but the patient, persistent search for it.

And he made that hero himself.

The Genre as Confession

Here’s a question that should trouble anyone seriously interested in Lovecraft: Why did the master of cosmic horror spend so much time writing dream fantasies?

And here’s the more uncomfortable follow-up: Why did he write his longest, most ambitious dream fantasy—The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath—and then refuse to publish it, dismissing it as merely “unpolished”?

The answer reveals something profound about the relationship between genre choice and emotional honesty. When Lovecraft wrote horror, he was protecting himself. When he wrote fantasy, he was confessing.

The Public Mask: Cosmic Horror as Emotional Armor

Lovecraft’s horror fiction is brilliant precisely because it’s controlled. The cosmic dread, the unknowable entities, the protagonists driven to madness—these elements create a perfect emotional distance. The narrator suffers, but Lovecraft remains safe behind the page. The protagonist loses his mind confronting Cthulhu, but Lovecraft gets to observe from outside the frame.

Horror allows for displacement. You can work through your deepest fears—of heredity, of decay, of social contamination, of loss—without ever admitting they’re your fears. The genre itself provides plausible deniability. “It’s just a scary story. Don’t read too much into it.”

Consider “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” where the protagonist discovers his heritage is tainted, that he’s becoming something monstrous, that his very bloodline is corrupt. This is clearly working through Lovecraft’s anxieties about ancestry, degeneration, and identity—but it’s working through them at a remove. The fish-people aren’t real. The story is a metaphor. Lovecraft can explore these terrors without owning them.

The cosmic horror framework also reinforces Lovecraft’s public philosophy. If the universe is meaningless, if humanity is insignificant, if knowledge leads to madness—well, then nothing really matters, does it? Including Lovecraft’s own fears, failures, and longings. The horror stories support the defense mechanism: it’s all meaningless anyway.

The Private Truth: Fantasy as Vulnerability

But fantasy—specifically, the dream-fantasy of the Dunsanian tradition that Lovecraft loved—doesn’t offer the same protections.

When you write about a hero questing for beauty, you’re admitting that beauty matters. When you write about friendship and loyalty saving the day, you’re admitting that relationships have value. When you write about someone searching for a lost paradise, you’re admitting that you long for paradise too.

Fantasy is inherently sincere. It requires the writer to commit to the idea that some things are worth seeking, that virtue exists, that meaning can be found. You can’t write a genuine quest narrative while maintaining ironic distance—the genre won’t allow it.

This is why Dream-Quest is so revealing. Lovecraft drops his armor. He writes about Randolph Carter seeking beauty, forming friendships, showing compassion, enduring hardships because the goal matters. There’s no cosmic indifferentism here. There’s yearning, and yearning is always vulnerable.

What Horror Allows vs. What Fantasy Reveals

Think about what Lovecraft’s horror stories actually depict. They show us protagonists who suffer for their curiosity, knowledge that destroys rather than enlightens, isolation as the inevitable human condition, the past as a source of contamination and dread, and beauty as merely a mask over corruption. The emotional landscape is one of inevitable decay, where every discovery leads to dissolution and every quest ends in madness or death.

Now think about what Dream-Quest depicts. Here we find a protagonist who succeeds through virtue, knowledge that—while dangerous—can be navigated with wisdom, solitude enriched by meaningful alliances, the past as a source of wonder and value, and beauty as something real, worthy of pursuit, and ultimately attainable. The emotional landscape is one where persistence pays off, where kindness creates allies, where the search itself has meaning.

These aren’t just different stories. They’re different philosophies. Different emotional orientations toward existence.

The horror is what Lovecraft could safely publish, what fit the weird fiction market, what aligned with his public persona as a materialist intellectual. The fantasy is what he felt but couldn’t defend philosophically.

The Unpublished Confession

And this brings us to the most telling detail: Lovecraft never tried to publish Dream-Quest.

He wrote it in 1926-27, during a period of intense productivity. He was actively publishing other stories. He had regular markets for his weird fiction. But Dream-Quest? He called it “unpolished” and tucked it away. It wasn’t published until 1943, six years after his death.

Why?

The standard explanation is that he recognized its flaws—the purple prose, the episodic structure, the Dunsanian excess. And yes, the work has those qualities. But Lovecraft published plenty of flawed stories. He was desperate for money, for recognition. If he thought Dream-Quest could sell, he would have revised it and sent it out.

The better explanation is that it was too revealing. Too personal. Too honest about what he actually valued and longed for.

When you write horror about cosmic indifference, you can maintain your intellectual credentials. You’re a serious thinker, grappling with existential truth. But when you write fantasy about a hero who discovers that his childhood home is the most beautiful place in all of existence—that the ordinary streets of Providence contain more wonder than all the cosmic vistas combined—you’re admitting something dangerous.

You’re admitting that you care. Desperately. Sentimentally. Without irony or philosophical justification.

And for Lovecraft, who had built his entire public identity around detached rationalism, that admission was more terrifying than any cosmic entity.

Longing Reveals More Than Fear

Here’s the deepest truth about genre choice: fear can be universal and abstract, but longing is always specific and personal.

When Lovecraft writes about the horror of discovering you’re not fully human, that could be anyone’s fear. When he writes about ancient evils lurking in the ocean depths, that’s archetypal, mythic. His horror stories deal in primal terrors that transcend the individual.

But when he writes about Randolph Carter searching desperately for a sunset city glimpsed in dreams, when he describes the precise quality of light on colonial rooftops, when he has Carter choose memory and home over cosmic transcendence—that’s not universal. That’s Lovecraft. Specifically, personally, vulnerably Lovecraft.

You can work through fear and maintain your armor. You can’t work through longing without exposing your heart.

Dream-Quest is the work where Lovecraft’s heart is most exposed. Where what he loved—and how deeply he loved it—becomes undeniable. The dream-fantasy genre forced him to write toward beauty rather than away from it, to affirm value rather than deny it, to admit that some searches are worth completing.

The Two Lovecrafts, Finally Named

By now the pattern should be clear. There is the Cosmic Horror Lovecraft, the public mask, who constructed a worldview where the universe operates without meaning or purpose, where human concerns dissolve into insignificance against the backdrop of cosmic time, and where knowledge inevitably destroys those who seek it. In this version of Lovecraft’s philosophy, isolation represents the fundamental truth of human existence, the past serves only as a source of contamination and inherited horror, and everything—civilizations, individuals, meaning itself—slides inexorably toward decay and dissolution. This is the Lovecraft we’ve been taught to read, the one who fits comfortably into academic discussions of modernist pessimism and existential dread.

But there is also the Dream Fantasy Lovecraft, the private truth, who operated from an entirely different set of convictions. This Lovecraft believed that beauty is objectively real and worth pursuing across any distance, that friendship and loyalty possess a power that can reshape reality itself, that memory doesn’t just recall the past but actively preserves and sanctifies it, transforming loss into something eternal. For this Lovecraft, home represents not mere geography but a sacred center from which all meaning radiates, the past functions as a source of illumination rather than contamination, and certain things—certain places, certain relationships, certain moments of aesthetic perfection—genuinely endure beyond the reach of time’s erosion. This is the Lovecraft of the letters, the man who walked Providence’s streets at midnight communing with ghosts, the mentor who poured hours into encouraging young writers he would never meet.

The academic establishment has canonized the first Lovecraft and dismissed the second as juvenilia, as a phase he outgrew, as secondary work not worth serious attention. But this is a fundamental misreading of the man and his art.

The dream fantasies aren’t what came before his mature horror—they’re what existed alongside it, in tension with it, as the emotional truth that his cosmic pessimism could never quite erase.

Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath is Lovecraft’s longest work in the dream-fantasy mode, his most sustained attempt to write from that place of vulnerable longing. And the fact that he couldn’t bring himself to publish it tells us everything: this was the work that mattered too much.

Horror was his job. Fantasy was his confession.

And confessions, by definition, tell us more than official statements ever could.

The Structural Achievement

Critics who dismiss The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath as juvenilia or an overlong indulgence often focus on its surface qualities—the Dunsanian prose style, the episodic pacing, the seeming lack of the tight narrative control that characterizes Lovecraft’s best horror stories. But this criticism fundamentally misunderstands what Lovecraft was attempting to achieve.

Dream-Quest isn’t just emotionally honest or philosophically revealing—it’s formally ambitious in ways that his horror fiction never attempts. This is Lovecraft reaching for something larger, more architecturally complex, more philosophically integrated than anything else in his body of work. The academic establishment has judged it by the wrong standards, measuring it against the compressed intensity of his short horror pieces when it should be evaluated as something else entirely: a complete cosmology given narrative form.

The Scale of Ambition

Dream-Quest is Lovecraft’s longest work, and that length isn’t accident or excess—it’s commitment. At roughly 30,000 words, it dwarfs his other fiction. “At the Mountains of Madness” comes closest at around 22,000 words, but that’s still a novella depicting a single expedition with a unified trajectory. Dream-Quest operates on a completely different scale, tracing Carter’s journey across multiple realms, through dozens of encounters, involving scores of characters and locations.

This isn’t just “more story.” It’s Lovecraft demonstrating sustained creative vision, maintaining thematic coherence across a narrative that encompasses the entire geography of dream. He’s not writing a tale; he’s writing an odyssey. And odysseys, by their nature, require scope. They require the reader to journey alongside the hero through varied landscapes, to accumulate experience and wisdom gradually, to feel the weight of distance traveled.

The length serves the emotional purpose: by the time Carter reaches Kadath, we’ve traveled with him so extensively that we understand, viscerally, what this quest has cost him. The revelation that his goal was home all along lands with power precisely because we’ve followed him so far from it.

The Synthesis of Mythology

What Dream-Quest accomplishes structurally that no other Lovecraft work approaches is the complete integration of his dream-cycle mythology. He had been building this world since his earliest Dunsanian fantasies—”The White Ship,” “The Cats of Ulthar,” “Celephais,” “The Other Gods”—but they existed as fragments, individual glimpses into a larger world.

Dream-Quest brings all of it together. The cats of Ulthar appear as Carter’s crucial allies. The ghouls, introduced in “Pickman’s Model,” become complex characters with their own culture and motivations. The city of Celephais and its dreamer-king Kuranes receive their fullest treatment. The gods of dream, the nightgaunts, the moon-beasts, the zoogs—all the strange inhabitants of Lovecraft’s unconscious geography converge in a single narrative.

This is world-building on a scale Lovecraft never attempted elsewhere. His horror stories take place in our world, with occasional glimpses of cosmic horrors beyond. Dream-Quest inverts that ratio: it takes place entirely in the other world, with the revelation of our world (Providence) as the final, transformative insight.

What Lovecraft achieves here is the creation of a genuine secondary world, as complete and internally consistent as Tolkien’s Middle-earth or Dunsany’s own dream-kingdoms, but inflected with Lovecraft’s particular obsessions. The dreamlands aren’t arbitrary or whimsical—they operate according to their own logic, their own hierarchies, their own rules of cause and effect. Carter can navigate them precisely because they’re real within the story’s ontology.

The Quest Narrative as Philosophical Argument

The structure of Dream-Quest follows the classic hero’s journey: departure, initiation through trials, and return. But Lovecraft uses this ancient narrative architecture to make a philosophical argument that his horror stories can’t accommodate.

In a typical Lovecraft horror story, the structure is revelation followed by collapse. The protagonist investigates, discovers terrible truth, and is destroyed or transformed by that knowledge. The narrative movement is always downward, toward disintegration. Even when the protagonist survives physically, they’re broken psychologically. The structure itself reinforces cosmic pessimism: seeking leads to suffering, knowledge destroys, the truth is unbearable.

But the quest narrative requires the opposite movement. The hero must grow through trials, must gain allies and wisdom, must achieve something meaningful through their journey. The structure demands that persistence pays off, that virtue leads to success, that the goal—however transformed by the journey—is ultimately attainable.

By choosing the quest structure for Dream-Quest, Lovecraft commits himself to a fundamentally optimistic narrative architecture. He can’t have Carter destroyed by his quest without betraying the genre. The form itself demands that Carter succeed, and that his success means something.

This is why the ending is so crucial. Carter doesn’t just survive—he achieves understanding. The revelation that Kadath is Providence, that the sunset city is his childhood home transfigured by memory, doesn’t negate the quest. It completes it. The journey was necessary precisely to teach Carter how to see what was always there.

The structure makes a philosophical claim that Lovecraft’s cosmic horror cannot: that seeking is worthwhile, that wisdom can be gained through experience, that beauty—once found—endures. The narrative architecture itself argues against cosmic indifferentism.

The Retroactive Transformation

One of the most sophisticated structural achievements in Dream-Quest is how the ending reframes everything that came before. When Carter discovers that his goal was Providence all along, the entire preceding narrative transforms in meaning.

Every landscape he crossed, every ally he gained, every hardship he endured—all of it was necessary not to reach some distant paradise, but to learn how to properly value what he already possessed. The dreamlands weren’t a path to Kadath; they were a path to understanding. The city wasn’t hidden in some remote cosmic location; it was hidden in plain sight, obscured only by familiarity.

This is architecturally sophisticated in a way that Lovecraft’s horror stories rarely attempt. His horror works through accumulation and revelation, building toward a climactic disclosure that recontextualizes what came before. But that recontextualization is always destructive—the truth reveals that things were worse than they seemed.

Dream-Quest performs the opposite operation. The revelation elevates rather than destroys. It doesn’t tell us that Carter’s quest was meaningless; it tells us that meaning was present all along, just misunderstood. The entire narrative, in retrospect, becomes a meditation on how we often fail to recognize the sacred in the familiar, how we project our deepest desires onto distant horizons when they’re waiting in the places we’ve always known.

This is the kind of structural complexity that makes Dream-Quest not just personally revealing but formally accomplished. Lovecraft is doing something technically difficult: he’s constructing a narrative that works on initial reading as a straightforward quest, but on reflection reveals itself to have been about something else entirely.

The Architecture of Memory

If we understand Dream-Quest as Lovecraft’s attempt to create a complete artistic statement about the relationship between dream and reality, between longing and fulfillment, between cosmic scope and personal meaning, then its structure becomes not just ambitious but necessary.

The work is long because the argument requires scope. It synthesizes his entire dream mythology because the argument requires completeness. It follows the quest structure because the argument requires affirmation rather than negation. And it ends with the revelation of home because the argument requires that the cosmic and the personal, the vast and the intimate, be reconciled rather than opposed.

What Lovecraft constructs in Dream-Quest is nothing less than an architecture of memory—a narrative structure that demonstrates how the past, properly understood, can be recovered and inhabited, how beauty persists despite time’s passage, how meaning can be found not beyond the world but in it, if we learn to see correctly.

His horror stories are brilliant, but they’re built for claustrophobia, for the gradual constriction of possibility until only dread remains. Dream-Quest is built for the opposite: for expansion, for possibility, for the gradual revelation that what we seek isn’t absent but present, not lost but preserved, not beyond reach but waiting where we started.

This is why comparing Dream-Quest to “The Call of Cthulhu” or “The Colour Out of Space” misses the point. Those are perfect horror stories—tight, controlled, devastating. But they’re not attempting what Dream-Quest attempts: to create a complete world, to argue through structure rather than just statement, to reconcile Lovecraft’s two selves in a single work.

The supposed flaws—the length, the episodic structure, the lack of tight horror pacing—aren’t failures of execution. They’re features of the ambitious project Lovecraft set himself. He was building something larger than a story. He was building a cosmology that could contain both his cosmic pessimism and his profound nostalgia, both his materialism and his mysticism of place.

And he succeeded. The fact that he couldn’t publish it, that he called it “unpolished,” that critics have dismissed it—all of this speaks not to the work’s failure but to how unprecedented and personal it was.

Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath isn’t Lovecraft’s most polished work. It’s his most complete one.

The Private vs. Public Lovecraft

We’ve traced the contradiction at the heart of Lovecraft’s life and work: the cosmic pessimist who lived a meaning-saturated existence, the materialist who treated Providence as sacred, the prophet of indifference who poured his soul into friendships and mentorship. We’ve seen how Randolph Carter embodies Lovecraft’s idealized self, how the choice of fantasy over horror represents confession rather than evasion, and how the structural ambition of Dream-Quest attempts something his horror fiction never could.

Now we must address the central question directly: If The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath reveals so much about Lovecraft, if it synthesizes his mythology and resolves his philosophical contradictions, if it represents his most complete artistic vision—why has it been so consistently undervalued?

The answer lies in understanding which Lovecraft we’ve chosen to canonize, and why.

The Lovecraft We Wanted

The twentieth century needed a prophet of cosmic horror. As the old certainties collapsed—religious faith, political stability, faith in progress—modernist literature sought artists who could articulate the new existential condition. Lovecraft fit the role perfectly: the atheist materialist who saw through human pretensions, who recognized our cosmic insignificance, who understood that the universe operated without reference to our hopes or fears.

This Lovecraft was useful. He could be taught in universities alongside Kafka and Beckett as an explorer of existential dread. His cosmic indifferentism aligned with the philosophical currents of the age. His horror stories provided vivid dramatizations of meaninglessness, perfect for academic analysis. He became, in effect, the weird fiction equivalent of a serious modernist—someone grappling with the death of God, the failure of reason, the emptiness at the heart of existence.

And to preserve this image, certain works had to be minimized or dismissed. The dream fantasies, with their earnest questing and affirmation of beauty, didn’t fit the narrative. They suggested a Lovecraft who still believed in something, who found meaning in memory and place, who couldn’t quite commit to the nihilism his cosmic horror seemed to preach.

Dream-Quest, as his longest and most emotionally vulnerable dream fantasy, was especially problematic. So it became “juvenilia,” a “Dunsanian pastiche,” an “unpolished draft”—something to be acknowledged in comprehensive studies but not taken seriously as a major work.

The Lovecraft Who Actually Lived

But if we attend to Lovecraft’s actual life rather than the persona useful to academic criticism, a different picture emerges.

This was a man who wrote thousands of letters, maintaining an enormous network of correspondents. Who walked the same Providence streets night after night, year after year, treating them as sacred ground. Who wept over demolished colonial houses. Who mentored young writers with extraordinary generosity. Who found his deepest joy not in cosmic speculation but in architectural details, in historical continuity, in the preservation of memory.

His letters reveal someone whose emotional life revolved around attachment—to place, to friends, to the past, to beauty. In a 1934 letter to R.H. Barlow, he confessed that his young friend was “as close to kin as one not bound by blood can be.” To Frank Belknap Long, he wrote that their correspondence was “the brightest moment of my day.” About Providence, he declared simply and absolutely: “I am Providence.”

These aren’t the words of someone who truly believed nothing matters. They’re the words of someone who cared so deeply that he needed cosmic indifferentism as a defense mechanism—a philosophical framework that would allow him to survive in a world that constantly threatened what he loved.

The cosmic horror was his armor. The dream fantasy was his heart.

The Work That Bridges Both Selves

What makes Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath Lovecraft’s crowning achievement is that it’s the only work where both selves appear fully integrated, where neither the cosmic pessimist nor the sentimental mystic completely dominates, where the tension between them becomes the story itself.

Carter seeks transcendence beyond the known world—this is the cosmic impulse, the desire to escape human limitation. But he finds transcendence in the familiar and ordinary—this is the sentimental impulse, the recognition that meaning inheres in the specific and personal. The dreamlands are vast and strange and filled with cosmic powers—but they serve ultimately to teach Carter how to properly value his childhood home.

The work doesn’t resolve the contradiction by choosing one side. It resolves it by demonstrating that both truths can coexist: the universe is vast and indifferent, and your particular corner of it can contain all the meaning you need. The cosmos cares nothing for Providence, and Providence is sacred. Both things are true simultaneously.

This is sophisticated philosophy disguised as fantasy adventure. It’s Lovecraft admitting that his cosmic horror and his nostalgia aren’t opposed but complementary—that the very vastness and indifference of the cosmos is what makes our small beauties precious, what makes memory worth preserving, what makes home sacred.

In his horror stories, cosmic scale negates human meaning. In Dream-Quest, cosmic scale intensifies human meaning by contrast. The bigger and stranger the dreamlands become, the more Carter’s childhood streets shine with significance.

Why It’s His Crowning Achievement

If we accept that an artist’s greatest work is the one that most fully expresses their complete self—not their most polished persona, but the full complexity of who they were—then Dream-Quest surpasses everything else Lovecraft wrote.

It contains his full emotional range in ways his horror stories don’t. Terror, yes, but also wonder, longing, friendship, compassion, determination, and ultimately joy—the joy of homecoming, of recognition, of finding what you sought in the place you began. His horror stories are emotionally monochromatic by design; they explore variations of dread and revulsion. Dream-Quest explores what it means to be fully human, which includes but isn’t limited to fear.

It resolves his central philosophical contradiction not by choosing sides but by showing how cosmic indifference and profound personal meaning can coexist without canceling each other out. This is more intellectually honest than either his pure horror or his pure fantasy because it acknowledges the tension Lovecraft actually lived with.

It’s autobiographical without being confessional in the limiting sense. Carter is Lovecraft, but mythologized, elevated, heroic. The work reveals Lovecraft’s inner life without reducing to mere personal disclosure. It transforms autobiography into mythology, which is what great art does.

It represents his highest ambition—not to write another horror story or another dream fantasy, but to create a complete cosmology that could contain all his contradictions, all his loves, all his fears, and all his longing in a single narrative.

And finally, it’s the work he couldn’t bring himself to publish, which suggests it mattered too much. The horror stories were his career, his public output, his marketable product. Dream-Quest was too personal to expose to commercial judgment. He called it “unpolished” not because it failed his literary standards—he published plenty of rough work when he needed money—but because polishing it would have meant confronting what it revealed about him.

The Invitation

The academic establishment has spent decades canonizing Cosmic Horror Lovecraft while dismissing Dream Fantasy Lovecraft as a minor footnote. But this creates a distorted picture of the artist. It gives us half the man, the half that fits contemporary critical preferences, while suppressing the half that doesn’t.

If you’re coming to Lovecraft for the first time, you deserve to meet the complete artist. And that means starting not with “The Call of Cthulhu” but with The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath.

Start with the work that shows you both Lovecrafts—the materialist and the mystic, the cosmic pessimist and the devotee of place, the prophet of meaninglessness and the man who found infinite meaning in Providence’s colonial streets. Start with the work where his virtues are on full display: persistence, compassion, diplomatic skill, the capacity for friendship, the recognition that home is sacred.

Start with the work where the hero succeeds rather than fails, where knowledge leads to wisdom rather than madness, where the quest—however strange and difficult—proves worthwhile.

Start with the confession rather than the armor.

Because here’s what the academic establishment has missed: Lovecraft’s cosmic horror is brilliant, influential, and formally accomplished. But it’s also limiting. It explores one note, however powerfully. It gives us Lovecraft the intellectual, the theorist, the architect of dread.

Dream-Quest gives us Lovecraft the human being—flawed, contradictory, deeply feeling, profoundly attached to beauty and memory and place. It gives us the man behind the cosmic pessimism, the heart behind the horror.

And that man, that heart, that vulnerable and sincere engagement with longing—that’s the Lovecraft worth knowing most of all.

The Rough Masterpiece

Yes, Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath is rough. The prose is sometimes purple, the pacing episodic, the Dunsanian influence heavy. It lacks the controlled intensity of Lovecraft’s best horror. It wouldn’t satisfy readers looking for tight narrative economy.

But these “flaws” are the evidence of its authenticity. Lovecraft didn’t polish this work because polishing would have meant distancing himself from it, applying conscious craft to something that needed to remain close to the unconscious source. The roughness is the proof of its importance—it mattered too much to perfect.

A masterpiece doesn’t have to be flawless. It has to be necessary—the one work the artist had to create, the one that contains what couldn’t be expressed any other way.

For Lovecraft, Dream-Quest was that work. It’s where he admitted what his cosmic horror denied: that beauty is real, that home is sacred, that memory preserves rather than contaminates, that friendship matters, that virtue leads to success, that meaning can be found not beyond the world but in it.

It’s where he confessed that Providence—his Providence, the city of his dreams and memories—contained everything he needed. That the sunset city he’d been seeking his entire life was waiting in the place he’d always been.

It’s where he finally let Randolph Carter—his idealized self—win.

This is Lovecraft’s crowning achievement not despite its roughness, but because of what that roughness reveals: a heart too full to be contained by cosmic indifferentism, a soul too attached to beauty to sustain detachment, a mystic of memory and place who could never quite believe his own philosophy of meaninglessness.

The academic critics dismissed it as juvenilia because it didn’t fit the Lovecraft they needed. But if you want to meet the Lovecraft who actually lived, who walked Providence’s streets at midnight communing with ghosts, who poured his soul into letters and friendships, who found meaning in every cobblestone and colonial cornice—

Read The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath.

That’s where he left his truest self, unpolished and complete.

Member discussion: