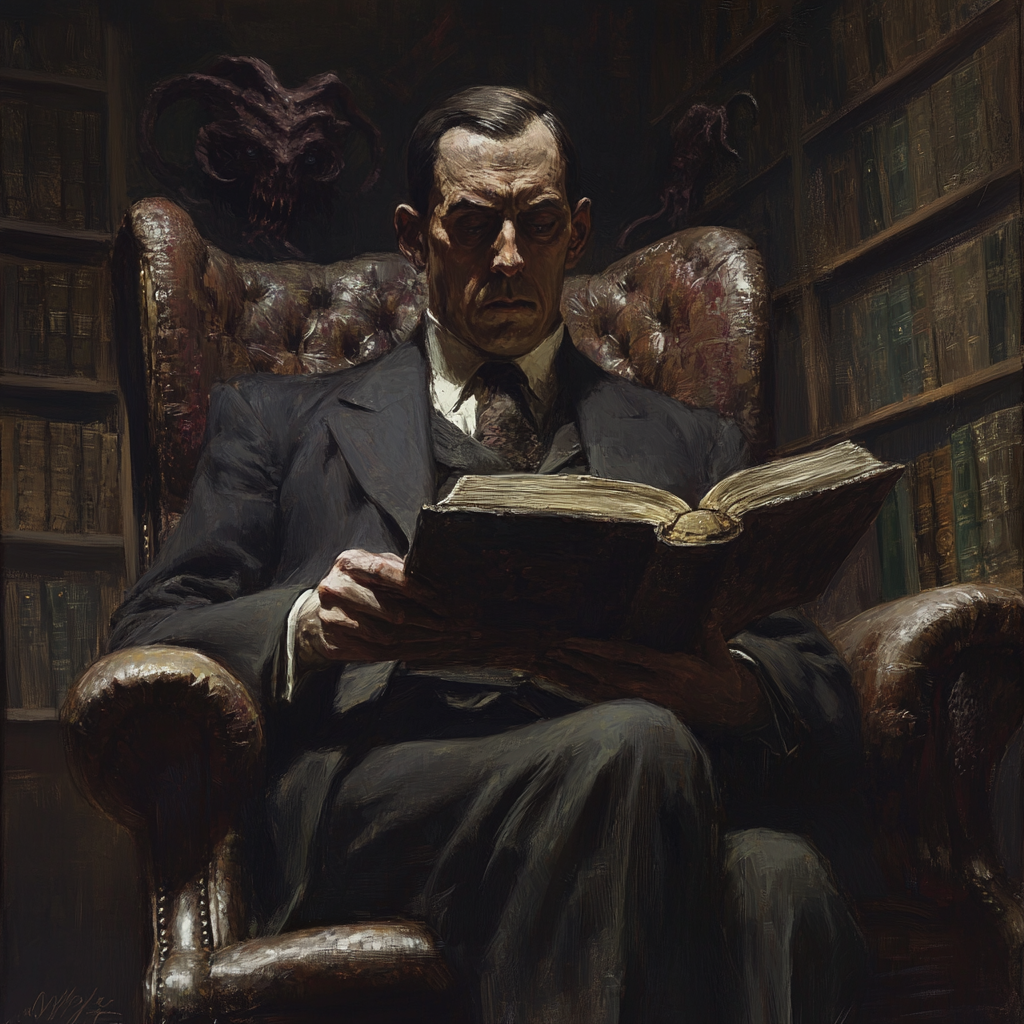

It is one of the great ironies of the modern occult revival that Lovecraftian Magic can trace its lineage not to an esoteric tradition, but to the coldly atheistic pen of Howard Phillips Lovecraft, a man who openly despised religion, ridiculed spiritualism, and regarded the occult with suspicion.

Subscribe to continue →From Cosmic Horror to Occult Practice ~ The evolution of Lovecraftian magic